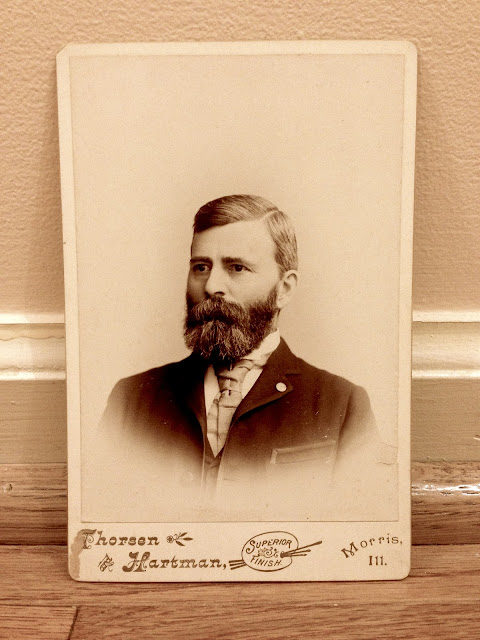

I think that one of the main reasons I am drawn to antiques, thrift stores, victorian houses and so on, is because they all tell a story. Usually the story is vague and sometimes it's more clear, but rarely is it complete... there's always room for a little imagination. To me, gathering clues from artifact(s) is like taking the time to put together a puzzle even though you know ahead of time that you may not have all of the pieces. Even with the missing pieces, however, you can still envision the entire picture, even if it isn't completely accurate. The picture that I'm referring to, of course, is a picture of someone or something's past. Be it a man on a cabinet card, an old journal, or a room in a house - everything has a story to tell. Sometimes, you really don't have any pieces of the puzzle... often times I'll pick up an item in an antique store that I'm drawn to and there is very little to go off of (for someone who isn't trained in dating or referencing old artifacts). But that's where your imagination comes in! To me, just knowing that an item is an antique is enough to get my interest. The fact that the item in my hand was at one point perhaps something very sentimental or dear to someone many years ago is pretty neat.

It is for this reason that I was especially drawn to a recent article on

Collectors Weekly. They wrote about an ongoing project in which the purpose was to investigate suitcases from an abandoned insane asylum in New York called Willard Asylum.

According to the article, the people who worked at Willard didn't know what to do with their patients' suitcases in the event that the patient had passed away (many of the patients did not have relatives to claim them), so they simply stored them in the attic. Photographer Jon Crispin got word of these abandoned suitcases, which had been at the New York State Museum, and started a petition to allow him to photograph the contents of each suitcase. It is clear from reading the interview that Crispin, (who reached his fundraising goal and will be displaying his photographs at the San Fransisco Exploratorium within the next year) grew very attached to each suitcase. Like myself, he felt as though each suitcase and each item had a story to tell. In the article he describes that sometimes the stories of patients that he uncovered were sad, sometimes scary, and sometimes even humorous. In a video on Crispin's initial

Kickstarter page he describes the items in the suitcases in the same way that I feel about antiques: "they're not just 'things', they're parts of people's lives".

from

Jon Crispin's wordpress

It seems that Jon isn't the only one, however, who has taken an interest in these abandoned Willard suitcases. Darby Penney and Peter Stastny, along with photographer Lisa Rinzler have also taken the time to go through a number of the suitcases in the attic. They've published a book, titled

The Lives They Left Behind: Suitcases From a Hospital Attic and they have an interactive

website where you can see photographs as well as detailed accounts of some of the patients and their belongings. Reading through the suitcase owners biographies on the website, it shocks me how few of them actually seemed to

really need to be admitted to an insane asylum. Of course, psychiatric standards have changed dramatically in the last 60 years, but it's still fascinating to read why some of the patients were admitted. Both the latter-mentioned website and the article from Collectors Weekly reference one suitcase in particular that belonged to a man named Frank. Frank was admitted to a mental institution because he had one angry outburst a restaurant over a broken plate. Looking at his photographs, I am saddened by his story and by many of the stories of the other patients. It is almost as though their lives were changed over night - at one point they were happy and thriving and then in a blink of an eye they end up permanently institutionalized. If they were not already ill during admission, then they became so simply due to anxiety or treatment. The staff at Willard, however, was known to be generally accepting towards their patients, so that is somewhat reassuring.

These suitcases are, in my opinion, the perfect way to get to know these people, and Jon Crispin seems to think along these lines as well. The patients who were admitted often brought only their most valuable possessions - those that they held most dear to them. It is not through medical notes or just documentation that you really get to know a person, but through artifacts such as these. These suitcases inspire me because they remind me why I love spending hours sifting through dusty "crap" in antique stores or taking the time to learn about someone in a photograph.

Every single person, dead or alive, has a story that deserves to be told... and I love being one to listen.